In 2014, University of Pennsylvania track and field freshman Madison Holleran took her own life because she felt she could not handle the pressure to maintain her high GPA while competing at the Division I level.

Nearly 11 months later, the same situation struck Penn athletics again after men’s track and field athlete Tim Hamlett, ended his life after feeling pressured to do well in an unfamiliar event.

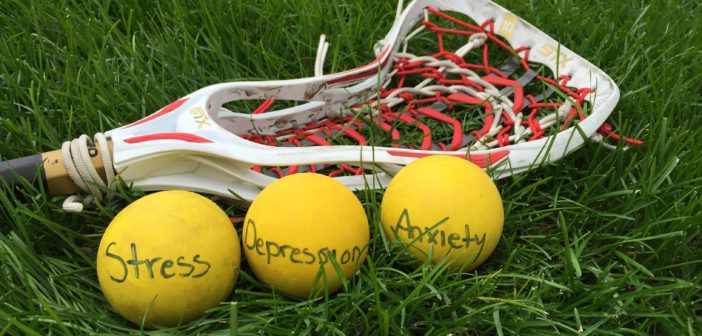

Athletes understand that playing through physical injury can have long-term effects or end a career, but what many do not understand is that playing through untreated mental illness can impact their life just as much.

According to a study conducted by the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, nearly 40 million adults in the United States suffer from anxiety disorders, requiring medication, therapy, and even hospitalization in severe cases. A group of that number includes men and women, ages 18 to 23, who face not only the pressures of being college students but also student athletes.

As the NCAA states in its Managing Student Athlete Mental Health Issues handbook, people — the athlete included — are most concerned with physical health and how it impacts performance. But the cases of Holleran and Hamlett show that what we see on the outside is not the only thing going on in an athlete’s life.

The pressures athletes face go beyond being able to perform and add little “W’s” in the win column at the end of the season. These pressures carry over into their dorm room, personal lives, and classroom.

“The transition from high school to college can be really difficult,” said North Central College sport psychologist Tara Savino. “In high school, they had someone checking in on them to make sure they got assignments done. In college, it’s on them.”

Savino likes to use “The Triangle” as a tool when working with student athletes. The mechanism includes the three main segments of a student athlete’s life — sport, school, social — and helps them figure out the balance among the three.

Time management is key, in Savino’s eyes, to staying on track with everything going on in a student athlete’s life and breaking down the hours in the week is a good first step to prioritizing. There are 168 hours in a week; of those, the average college student aims for eight hours of sleep per night, adding up to 56 hours per week. With a full course load of four classes, students spend roughly 24 hours sitting in class or doing homework, class projects, or studying. This totals 80 hours of used up time, nearly half of the number of hours in a week. Those other 88 hours are free for students to work jobs, have social lives, and spend time with family and friends.

For student athletes, those additional 88 hours dwindle fast. Practices and team training total 20 hours a week. That doesn’t even include travel time where athletes can be off campus anywhere from four hours to days on end, adding up to almost 15 hours a week. That leaves only 53 hours for student athletes to try and fit in everything else.

And like other students, many have at least one part time job to add into the mix. The hours in the week start ticking away and many student athletes begin to feel the pressures taking a toll on their body and mind.

Unfortunately, athletes may not recognize the signs and symptoms of mental illness until they has consumed them.

Today, mental illness is often overlooked, largely in part due to stigmas and a lack of awareness. Because we cannot always see the damage, it does not mean it is not there.

“It’s hard with the stigma attached to it,” said Bri Johnson, a sport psychologists who works with Savino. “It’s easy to see someone with a physical injury and say ‘oh, you’re injured.’ But [mental health]is serious and clinical. What the athletic trainers do for the body, we do for the mind. You wouldn’t tell someone with a broken leg to go out there and suck it up. The same mentality should go with anxiety and depression as well.”

Sometimes, a little time off is what the athlete needs. While sport can be an outlet, it can also be the trigger, in which case the athlete would benefit from taking a step back. Arika Cozzi, an athletic trainer from Athletico who also works at North Central, knows that it’s not always as easy to notice as a physical injury, but something that athletes need to be aware of not only in themselves but in their teammates as well.

“If any athlete has a history of mental illnesses, we like to follow-up with the patient,” said Cozzi. “For instance, we want to make sure if the patient is seeking adequate care from the appropriate health care. We do have training in how to calm patients down if they are having an emergency and act as another referral source to the appropriate mental health care professional.”

And that’s where Savino and Johnson come in to play. Their jobs are to not only help individuals conquer anxiety and depression, but to bring awareness to mental illness by working with teams and individuals to learn time management.

When working with teams, Savino says she likes to make it comfortable for both those who may suffer from mental illness and those who may feel uncomfortable talking about it. The words “issues” and “problems” are replaced with “challenges” and “obstacles” to connect with the competitive mindset of the athlete and keep a positive atmosphere in the session.

“One of the things we focus on with our athletes is that sport is not the whole, but a part,” said Savino. “If things are out of balance, it affects the whole, which is why it is important to not only make sure the body is healthy but also the mind. It doesn’t make you any less of an athlete or person to take a step back. Smart athletes do not play injured and that includes mental health.”

Johnson agrees. “Athletes worry that if they take a break and don’t play that they will be replaced or let down their teammates or coach,” she said. “We know that it is going to be a battle, but getting help and working through it now will make it better down the road.”