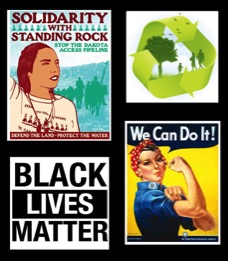

For every progressive action, there is a dissenting conservative reaction – such is the overarching theme of the 20th century Progressive Era, a movement that inspired arguably as much opposition as it did social change. This opposition, or cultural, political or social backlash against progressivism, backlash that permeated the political atmospheres of the feminist, environmentalist and civil rights movements, has reared its head again toward its most contemporary opponent: the police reform and social justice cause known as Black Lives Matter.

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement began as an organically simple yet meaningful phrase. Following the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the fatal shooting of black 17-year-old Travyon Martin in July 2013, a post by Facebook user Alicia Garza titled “a love letter to black people” took notice from social media users. Since then, those three words have symbolized solidarity with people of color as well as witness to a terrible disparity in America: black people are nearly eight times more likely to die of homicide than white people in the US.

The grassroots movement garnered immediate attention: according to Pew Research, the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter appeared almost 11.8 million times in mid-2013 following the July acquittal of Zimmerman. Today, the movement now serves at least 37 chapters across the country, as well as an international chapter in Toronto, Canada. It’s mission: to work for “a world where Black lives are no longer systematically and intentionally targeted for demise,” according to BLM’s official website.

Though not everyone agrees with this sentiment: about one-in-five Americans, roughly 22 percent of the population, oppose the BLM movement. Reacting to their rhetoric, opponents of BLM rallied around a countermovement now known incongruously as “All Lives Matter” – and like BLM, the phrase stuck. Since its coining, the hashtag #AllLivesMater has been used nearly 1.5 million times, about one-eighth as often as #BlackLivesMatter.

Though unofficially stated, proponents of ALM argue that, as its name would suggest, all lives and not only black ones have significance. However, this misconception regarding the intent of the BLM movement has been disproven with the addition of the word “too.” Black Lives Matter Too, is the counterargument of many supporters, allies and members of BLM. Chapter leaders, writers and cultural analysts have further explained and broken down this rhetoric: that by focusing on one marginalized group, all lives will be bettered further.

Though unofficially stated, proponents of ALM argue that, as its name would suggest, all lives and not only black ones have significance. However, this misconception regarding the intent of the BLM movement has been disproven with the addition of the word “too.” Black Lives Matter Too, is the counterargument of many supporters, allies and members of BLM. Chapter leaders, writers and cultural analysts have further explained and broken down this rhetoric: that by focusing on one marginalized group, all lives will be bettered further.

And yet, this opposition still stands, stubbornly firm, implying that groups are not only offended by this rhetoric, but by something else.

“Those that have strong reactions to (progressive movements) have been those that feel most threatened by the groups themselves,” says Dr. Suzanne Chod, North Central College of political science. According to Chod, when an oppressed, marginalized group becomes included within the American identity, the group in control, or the hegemony, may feel threatened. This unease results in rhetorical, political or, occasionally, legal backlash from powerful groups.

Historically in the US, the American hegemon has consisted primarily of white males, resulting in an overwhelming sense of white nationalism – a belief that “national identity should be built around white ethnicity, and that white people should therefore maintain both a demographic majority and dominance of the nation’s culture and public life.” Groups that threaten this idea of American nationalism, such as BLM, are ultimately backlashed.

“They (BLM) are attacking a powerful interest,” says Dr. Steve Macek, North Central College professor of communication. According to Macek, BLM challenges a “possessive investment in whiteness” – a privilege that statistically ensures higher employment rates and better quality of life in the U.S. In an economical give-and-take, BLM’s demand for better treatment would equivocally mean that white lives would need to relinquish certain privileges, such as accessibility to jobs. In a time of economical decline, anxiety among the working class has further stoked the fire against progressive movements, such as BLM, who wish to gain better employment opportunities for minorities and marginalized groups.

“While it is true that white Americans are better off… not all white people are doing well in recent years,” says Macek. “(As a result,) there has been a certain amount of resentment among white members of the working class.”

Political scientists use the term “rural resentment” to describe this shared indignation among members of America’s flyover states, or any inland states between the east and west coasts. Demographically rural and conservative, these areas are often overlooked by their more progressive, typically liberal coastal neighbors. The culmination of this resentment is ultimately displaced into progressive organizations that continue to threaten the conservative hegemony, such as BLM. Simply put, these groups demand the attention they feel they’ve been neglected; they’re political outcry: “But what about me? What about us?”

Though progressive movements have not gone silently into the night: In a twist of “backlashing the backlash,” critics of countermovements such as ALM argue that these groups are only ever reactionary in purpose and, therefore, cannot incite social change. According to Pew Research, contrary to the use of #BlackLivesMatter, social media posts that used #AllLivesMatter in a positive manner were less likely to connect their posts with a broader social agenda. More tweets were negative: roughly 13 percent of #AllLivesMatter posts from July 2013 to March 2016 were aimed at defending people or organizations criticized by the BLM movements. Another 13 percent of tweets focused solely on condemning the movement all together.

“All Lives Matter, I would say, is not really a movement,” says Dr. Chenjerai Kumanyika, Clemson University professor of critical cultural methods. “It’s a rhetorical device.”

Kumanyika cites the tragedy of Zachary Hammond, an unarmed white teen fatally shot in July 2015 by police. In an event that was eerily unnoticed by the media, ALM too remained silent. Rather, conservative publications under the guise of “all lives matter” took the opportunity to criticize the BLM movement once again, publishing headlines such as “Family Attorney: No Outrage When Shooting Victim is White” and “Unarmed White Guy Gets Killed by Cops, No One Cares.”

Critics further argue these countermovements invalidate the concerns of the specific groups they target, deeming them not only reactionary, but dangerous.

“When you say (a marginalized group) can’t ask for basic human rights… what you’re basically doing is dehumanizing those groups,” says Kumanyika. “And when you dehumanize those groups verbally through the media, then you’re setting the stage to… treat them as less. The larger public won’t care because you’ve already marginalized and dehumanized them.”

Though Americans have gained awareness to the disparities of marginalized groups in recent years, discrimination and, worse, ignorance, willful or otherwise, of such discrimination still exists in the 21st century. According to a Pew Research study, only 16 percent of white Americans said that black Americans experience “a lot” of discrimination in this country, though the black unemployment rate is roughly double that of whites.

“Black lives have been systematically devalued,” says Macek. “What (ALM) is really doing is denying that racism still exists.”

“I find the notion of ‘anti-movements’ deeply unsettling,” says Dr. Jennifer Jackson, associate professor gender and women studies. “I suspect they see themselves as nuancing what feels to them a blunt force, an unapologetic challenge to their beliefs, values and assumptions. However, their ignorance and arrogance remains offensive to those struggling for a voice in this country.”

Ironically, in the case of BLM, increased backlash has begun to galvanize support among allies and former critics of the movement. The recent election of conservative president-elect Donald Trump and vice president-elect Mike Pence, as well as an elected Republican House majority, has more or less proven a deeply strewn sense of white nationalism still among Americans today. Surfaced videos of police brutality, increased reports of racial slurs and the acceptance of a new government that openly mocks minority groups has all but made it impossible to deny contemporary racism, providing BLM and its contemporary progressive movements, a chance to reach others and to make a social difference.