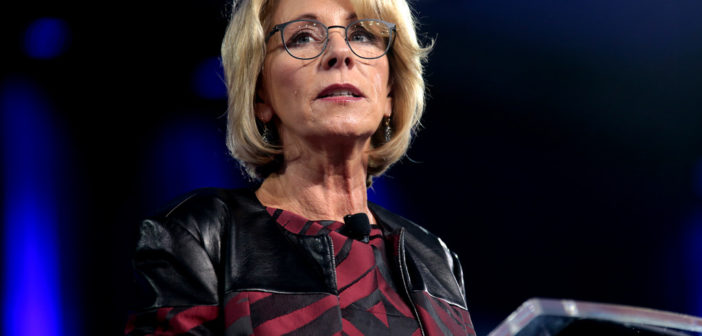

On the first day of fall 2017, the Department of Education, led by Secretary Betsy DeVos, released a “Dear Colleague” letter rescinding a 2011 letter that called for more strict guidelines referring to sexual assault and harassment investigations.

The Obama Administration’s Department of Education letter required higher-ed institutions to make judgments in their investigations based on a “preponderance of evidence,” meaning that the responding party is guilty if more than 50 percent of the evidence points that way, a lower standard than in criminal cases.

Reportedly, DeVos’ main concern with the system stemmed from that lower bar of guilt used in these cases. “The 2011 and 2014 guidance may have been well-intentioned,” reads DeVos’ department’s letter. “But it also has led to the deprivation of rights for many students – both accused students denied fair process and victims denied an adequate resolution of their complaints.”

The 2011 guidance also reframed sexual assault and sexual harassment as a discriminatory act that “interferes with students’ right to receive an education free from discrimination and, in the case of sexual assault, is a crime.”

People on the left and right of the political spectrum have argued if the 2011 letter took the appropriate action forcing colleges and universities to do a better job in these cases or if they went a step far in their regulation. In a statement the National Women’s Law Group called Devos’ comments on the issue during a speech at George Mason University on Sept. 7 “a blunt attack on survivors of sexual assault,” cases which have historically gone underreported on campuses.

“It’s going to have a chilling effect for survivors to come forward,” said Rebecca Gordon, North Central’s own Title IX coordinator. “Because it’s much harder to work through this system when it is by definition something that is occurred mostly between two people with no witnesses.”

Gordon, who is the first full-time Title IX coordinator at North Central, was hired a year and a half ago – in part due to the guidelines put into place by the 2011 Department of Education letter. But also, Gordon has 25 years of experience in the field of psychology, including work as a therapist for students on college campuses.

Gordon currently oversees cases and investigations involving Title IX at North Central where she works with seven deputy coordinators. She also works with campus advocates and the Dyson Wellness Center to make sure students receive the remedies and accommodations that they seek.

One of the main problems Gordon identifies with DeVos’ analysis of the 2011 letter is that it focuses on the few cases where schools got it wrong when, in her estimation, “many, many in fact most schools got it right.”

While she admits that the 2011 guidelines were not perfect, there were details that fundamentally reshaped her view of the way sexual assault and harassment is handled within the college campus. Most importantly, it was the rephrasing of those acts as a violation of a student’s civil rights that was a “game changer” for Gordon.

“I had sexual violence in a different bucket than sexual harassment and I did not think about the discriminatory impact of those experiences within a person’s life,” said Gordon. “It was really important for that reframing of the impact of those experiences on students, because I know firsthand.”

Gordon asserts that when you look at sexual assault through that lens, the measure of preponderance of evidence holds up because it is the standard that all other civil rights’ violations are evaluated at. Whether it be race, ethnicity, gender or sex, they are all handled at the same level.

“Why is that the only form of discrimination that is looked at a higher level?” asked Gordon.

The aspects of that 2011 letter that she did wish were clarified involve how schools go about getting it right like she prides herself that she and those she trains in her department work to do. Through training faculty and advocates to handle sexual assault and harassment investigations, her co-workers make sure both sides get fair resources and are assigned knowledgeable advocates.

However, DeVos revoking that letter does not make headway in solving those issues. “It’s like a flywheel,” said Gordon. “We’ve all been moving in a particular direction and so if they radically change what they’re requiring, yes, that’s going to sort of stop the momentum, and for most campuses, the good momentum in regards to training the people who respond to these issues as well as the general campus and the prevention efforts.”

Despite changes that DeVos makes to federal Title IX policy, thanks to an Illinois state bill in 2015 (HB0821), incidents on campuses in Illinois may still be held to the preponderance of evidence standard — for the time being.