When the discussion of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) comes up, what are the first drugs you think of? Steroids? Blood-doping? The reality is that the banned substances used by NCAA athletes tend to be drugs you wouldn’t even consider.

Since the information came out about the Russian doping scandal and eventually their Olympic ban, PEDs have been a prevalent topic of conversation in the athletic world. Despite the vigorous testing policies, banned substances still prove to be a problem among collegiate athletes. More recently, Florida State quarterback Will Grier was banned for a year after testing positive for an NCAA banned substance in 2015.

Taylor Arman, an instructor of kinesiology and athletic training coordinator of clinical education at North Central, defines what a PED is and how they can be hidden: “A PED is classified as anything that alters your ability to perform that increases your strength, increases your concentration or increases your reaction time. You know, that’s why the list is so extensive. I think where people get tripped up is they look at the list like ‘oh yeah, I’m not on any of that.’ The danger is that not everything is labeled appropriately and athletes are taking a supplement or going online and buying something and don’t know what’s in there.”

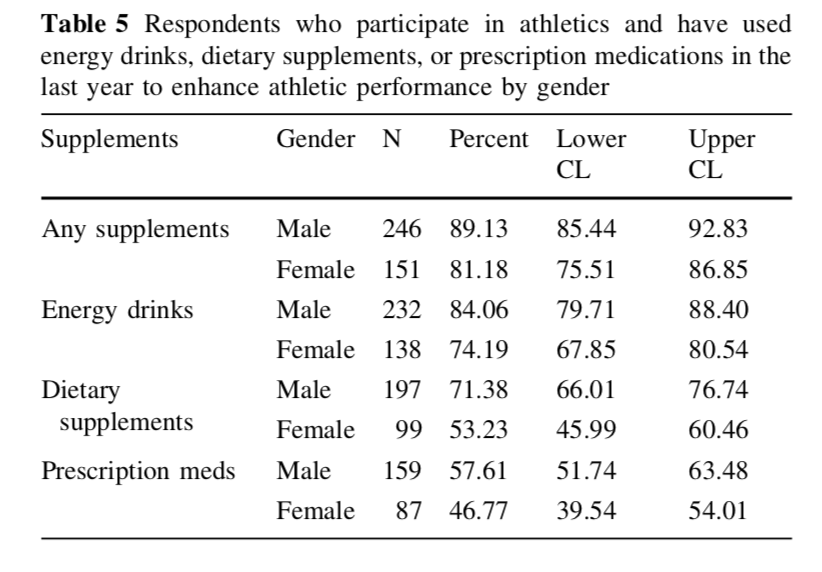

Student-athletes are now finding that additives like caffeine intake, dietary supplements or prescription medication are yet another way to enhance performance. A study from 2013 shows the data behind these banned substances and how college students are using them:

Though most of the banned substances athletes could be using don’t have any immediate life-altering effects, they do have some dangerous long-term effects. Dr. Patti Engel, assistant professor of biology, has studied the short-term and long-term effects of these substances. Engel said that people who are trying to enhance performance will use Epogen to boost the number of red blood cells in their circulation because it increases their oxygen carrying capacity and can enhance their performance in endurance in sports like cycling or distance running.

“The problem is that the body tightly regulates its natural levels of recovery. So, people are using Epogen and that drug is overriding what the body can naturally produce and that overrides natural negative feedback. So they start increasing the number of red blood cells and what happens is that the blood becomes very thick or viscous so they use other ways to try to bring that down. This can cause heart issues because of that viscosity of the blood,” Engel said. Use of drugs like Epogen can ultimately cause serious health risks such as heart disease, stroke and cerebral or pulmonary embolism.

For Ashley Eisenmenger, ’18, the topic of PEDs is a frequent conversation in her sport. Being an elite blind para-triathlete, Eisenmenger has experienced politics of PEDs firsthand. “In para-cycling (or para-triathlon) for a while, your guides weren’t being tested. So essentially what was speculated was that guides were doping like to assist their athletes especially because on a tandem (bike) you can be unequal in your effort and power distribution doesn’t really show,” Eisenmenger said.

In the last few years, guides are now subject to testing under the International Paralympic Committee codes as well as the World Anti-Doping Agency Codes. Eisenmenger also noted the extensive education elite athletes get from United States Doping Agency during their training. “They came in and basically educated us on how everything goes and how like you can essentially perform up to three tests on someone’s collected urine sample. So, they do a test and then you have the opportunity to ask for a retest if it comes back positive. You can say, I want to be present or say I designate this person to be present,” said Eisenmenger.

This is also true for NCAA athletes as well. Arman mentions that the process of testing is just as arduous when being tested at the collegiate level. North Central was the testing host for football playoffs seven years ago according to Arman, who was the head athletic trainer at the time.

During this process, athletes are randomly tested whether they actually play or not, and are fully educated about the testing process. The host school doesn’t know about the testing until the week of the testing and then the athletes aren’t notified until the game/race/match is over and they (the random selection) will be tested and have 10 minutes to produce a sample.

“They send people (NCAA) to campus and you have to set up rooms you have to turn off the water supply into the room. Somebody is examining the person producing a urine sample from a drug-free sport. The institution is more of just the host. When the teams arrive at campus, whether you’re the host school or the other competing school(s) is, the NCAA has to notify that point person (typically the head athletic trainer) who will be tested post-competition,” Arman said.

Regardless of the extensive testing process when it comes to professional or collegiate athletics, there are still athletes who fall through the cracks, whether it is finding a way around testing positive for banned substances or not having the knowledge of what you can or can’t use as an athlete.