“Ang hindi marunong lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makararating sa paroroonan.”

Translation: “One who does not know how to look back at where they came from will never get to their destination.”

– Jose Rizal, Philippine novelist and national hero

When I read the article by Jojo, Cynthia, and Matt, I recognized a parallel between their experience and my own discovery about two decades ago. I was an undergraduate student when I stumbled upon a hidden chapter in Philippine and American history that horrified me. The year was 2001, and I was celebrating my third year in America as an international student. While researching for a Political Sociology project in the Beloit College Library, I checked out a documentary on a major historical event that I never knew about: the Philippine-American War from 1899 to 1913.

I remember rewinding the VHS tape in my dorm room, watching it over and over again. It was difficult to fully comprehend what I saw and heard: pictures of American soldiers posing with their guns and bayonets as slain Filipinos lay on the ground; Americans calling Filipinos jackrabbits and niggers. No one knows the exact number, but at least 200,000 Filipino soldiers and civilians died in that war; some historians say up to a million. The American casualty was more than 4,200.

A race war

I dug deeper, learning that President Theodore Roosevelt racialized the conflict. In a 1902 speech, he declared that it was America’s duty to uplift and civilize the Filipinos, who lived in barbarism. It was a war “between the forces of ‘civilization’ and ‘savagery.’” (Kramer, The Philippine-American War as Race War). In 1899, British poet Rudyard Kipling wrote “The White Man’s Burden: The United States and The Philippine Islands”—which Roosevelt copied and sent to his friend, Senator Henry Cabot, commending its “expansion point of view.”

I encountered excerpts from letters of American soldiers writing home, one of which hit close to home, literally: “We bombarded a place called Malabon, and then we went in and killed every native we met, men, women, and children.” Malabon is my hometown, where I went to elementary school and learned that the Americans were our allies and saviors from the oppressive Spanish colonizers.

To this day, many Filipinos regard white Americans as culturally superior. I, for one, grew up ashamed of my flat nose; my sister continues to whiten her skin with all sorts of lotions; English remains the language of power; and many prefer American goods over native ones. This cultural inferiority complex, coined as colonial mentality, remains deep-seated in the Filipino psyche. It is an expression of the profound pain that Filipinos have internalized; a result of the trauma we collectively experienced during and long after the abusive American regime.

When I asked fellow Filipinos and my American friends about this war, no one knew about it. Imagine that: Americans WON this major war, and they didn’t know about it. They knew a lot about the Spanish-American War—where Filipinos fought as American allies—but not about the war that happened immediately after it, which propelled the United States to become full-fledged imperialists.

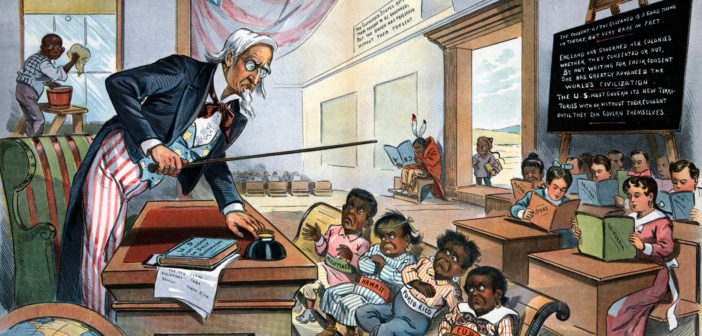

What makes this period in our shared history especially horrifying is the deceit that remains unacknowledged to this day. In January 1899, President McKinley proclaimed the “Benevolent Assimilation” policy, stating that they arrived in the Philippines as friends, to teach the Filipinos the art of self-government. The US refused to acknowledge the independent Philippine Republic, established by its first President Emilio Aguinaldo, who had led the Filipinos to gain independence by defeating Spain. Instead, they chose to infantilize and call us indios and savages (See political cartoons.)

What McKinley actually meant was that the US was there for business: they wanted the Philippines’ strategic geographic location, as well as to create a new market for American goods. Exactly one month after the proclamation, American soldiers started killing their supposed “little brown brothers.”

Reconciliation and recovery

So how did I reconcile this horrifying discovery with the fact that I have chosen to build a life in America? I practiced self-reflection and civic engagement, and began expressing pride in my cultural identity. Throughout my career and volunteer efforts, I chose to serve in my community, advocating for various marginalized groups: I ran after-school programs for low-income Chicago youth, served on the boards of Leadership Center for Asian Pacific Americans and Filipino American Network Chicago, raised funds for Filipino scholars in my native country, and wrote grants for various causes such as LGBTQIA advocacy, women’s issues, art education, disaster relief, and programs for military veterans and people with disabilities. Today, I am focused on helping empower students and women through my work at North Central College.

I am also working on a final project to complete my Master’s degree: a story cycle celebrating the richness of Philippine mythology. I intend to continue writing about the beauty of the Filipino culture, as a way to unlearn colonial mentality. For me, art is one of the most powerful ways to heal. It is also one of the ultimate weapons against societal problems.

After all, our Philippine national hero was a novelist whose books inspired a nation to revolt against its colonizers. As award-winning Filipino author Gina Apostol wrote once: “Some say the [Philippine] country is distinct because it was created by a novel—Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere.” Just this past November, Apostol published Insurrecto, a groundbreaking novel about the Philippine-American War. I believe hers is one of the most powerful contributions by any artist to our current generation and to many more after ours.

I recognize that it may take many generations to unlearn colonial mentality; what gives me hope is knowing that there are many others who are steadfastly working, in their own ways, to shed light on the truth and work towards a more just and compassionate world.

Lux Veritas

In the midst of many atrocities, we can always find enlightened people who chose to behave magnificently. In 1898, for example, a group of concerned citizens established the American Anti-Imperialist League. One of its famous members is Mark Twain, who published “To the Person Sitting in Darkness”—an outstanding example of how one can respond courageously, in defiance of all that is bad around him.

In 1899, African-American soldier David Fagen defected to the Philippine Revolutionary Army, eventually serving as its Captain. Like many of his peers who followed his lead, he battled with the moral dilemma of fighting in a racial war while continuing to suffer from Jim Crow laws at home.

More than a century later, our society is still plagued by structural racism and all kinds of power-based violence. Today, leaders such as Bryan Stevenson, founder of Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), continue to fight for racial justice. On April 26, 2018, EJI opened The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, America’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence. Stevenson believes that confronting the truth about our history is the first step towards recovery and reconciliation.

And finally, there are enlightened ones in our very own campus: Jojo, Cynthia, and Matt are just three of many bright young people who embody the college’s aspirational phrase in its seal: Lux Veritas. To you and those who follow your lead, I say: I support and applaud your integrity and courage as you continue to seek the truth. Thank you for confronting racism head-on. If the world is truly going to end hate and intolerance, it will need to rely on more leaders like you.