In her recent Netflix comedy special, comedian Whitney Cummings brings up the MeToo movement and the shift in what people deem appropriate in the workplace. This comes after a wave of sexual assault and harassment allegations, many of them directed toward members of the comedy community.

Is it too soon? Can she joke about that?

When Cummings was 19, she was forced into a director’s trailer. She talks about her escape from a possible sexual assault in her memoir.

“She didn’t tell her mother what had happened to her and that even in writing about it, she feels as if she’s ‘an ungrateful brat, a spoiled *sshole who doesn’t even know what being victimized is or what real sexual assault feels like,’” said Cummings in an interview with Bustle.

That “walk into the director’s room” is all too common for women in the entertainment industry. But, it is especially common for women in the comedy industry, where the gender disparity is exceptionally high.

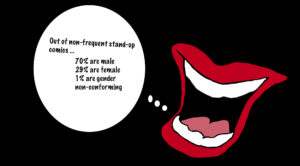

Meredith Kachel, a stand-up comedian and producer, ran a ten-month long study of performers in 19 comedy showcases around Chicago, which was published in a Chicago Reader article. For comics who performed less frequently, it was 70% male, 29% female and 1% gender non-conforming. The studies overall show that there is an imbalance in stand-up bookings. Men are favored over women.

Graphic by Madison Miller

“I do think that many women have to chameleon themselves as tough, or bawdy, or willing to undermine their female peers, or not live up to their values, to fit into the boys club. I think that many people’s biases on how lineups are based give women less opportunities to get on stage, though that is changing,” said Kachel.

That does not mean, however, that women are given equal opportunity or that they are even sometimes forced to give up their values to make it in the comedy world.

“But clubs will still have only one woman on their lineups, which means one woman per lineup with maybe three to five other men. Consider it comedy’s diversity hire,” said Kachel. “In my experience, I’ve watched many women piss off one man or a group of men who have some sway or pull in the scene and then be blacklisted from their shows, giving them less or different opportunities than they would have had. These are always due to an assumed slight. Even when women joke about the fact that there’s an imbalance, they’re mocked relentlessly.”

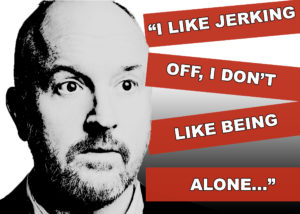

On April 4, Louis C.K. released an unexpected special for purchase and download on his website titled “Sincerely Louis C.K.”

Graphic by Madison Miller

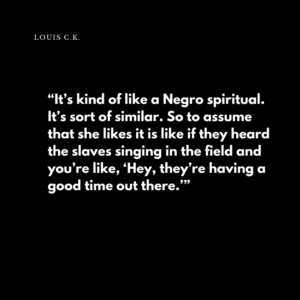

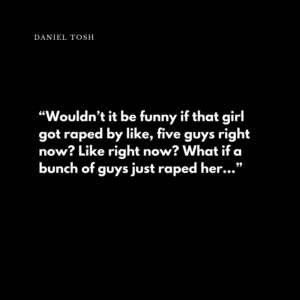

The special does not stray away from the accusations against him in 2017, which included forcing women to watch him masturbate. Instead, they become the butt of a joke. At one point, he compares a female’s consent to slaves.

“It’s kind of like a Negro spiritual. It’s sort of similar. So to assume that she likes it is like if they heard the slaves singing in the field and you’re like, ‘Hey, they’re having a good time out there.’”

Graphic by Madison Miller

The rest of his special is littered with jokes about necrophilia, pedophilia, terrorism and people with disabilities.

The questions here are: Who let C.K. back on stage? Should he be allowed back there? How do we decide that?

After the recent trial of entertainment mogul Harvey Weinstein who is now serving jail time, possibly more in the future, it seems like there is an unclear deciding line on who is punished for their crimes against women. It’s not all. It’s some.

According to an article from Vox, Weinstein walked right into a comedy show back in 2019. When actor Zoe Stuckless confronted him, she was escorted out instead of him. Comedy and power are interconnected.

“And the fact that Weinstein, whose name has become almost synonymous with allegations of sexual assault and harassment, was apparently protected by staff at a comedy club is a reminder that while plenty of powerful men have lost their jobs as a result of Me Too, the larger culture around gender and power in America has been a lot slower to change.”

That line seems to be comedy in this case. By creating jokes and centralizing problematic comments and behaviors into this container of “comedy,” it creates a first line-of-defense. Comedians hold a certain kind of power over us, as well as each other.

After posting a Reddit thread toward a group of stand-up comedians about what that line is and when it’s crossed — the verdict is this line is ever-changing, subjective, personal, invisible yet visible.

Dan Guiry ran a heckle show called “The Danger Room” in Toronto for four years. This is a show that allows the audience to make rude comments directed toward the comedian as a part of the overall experience.

“Buddy it was brutal … yes, there were lines that were crossed. That’s why I eventually stopped doing it … I had regular guests come and take it too far … But we actively encouraged lines to be crossed,” said Guiry. “We had a segment called the trigger words, where we had the audience put trigger words in a bucket. Then myself and the co-host would draw out the words and say them. It was actually pretty uplifting that part. It was just two problematic audience members that ended up ruining the show. Very racist with no jokes in their heckles.”

Heckling and harassment exist sometimes a little closer than people realize. For some comedians, it’s the fear of heckling-turned-harassment that keeps them from the stage altogether.

For other comedians, it’s the immediate fear of “cancel culture.” Comedians fear that one bad line or joke could lead to a tirade of hate, typically on social media. This would lead to their ultimate defeat and disgrace from the world of comedy.

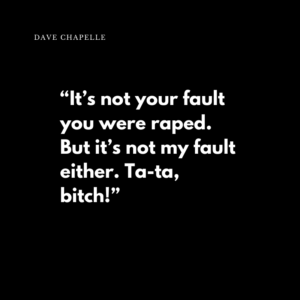

Comedian Dave Chapelle, according to an article from Vox, argues against cancel culture by saying, “‘What the fuck is your agenda, ladies?’ … He hints that the leftist political rhetoric that is considered the progenitor of cancel culture is to blame for our distraction from other big issues, like gun control.”

Although “canceling” people can be problematic, Chapelle has done his fair share of cancel-worthy-actions. He even made a joke to an offended fan as they were leaving his set, “It’s not your fault you were raped. But it’s not my fault either. Ta-ta, bitch!”

Graphic by Madison Miller

So, while comedians can be the enemies of people in the audience, it definitely can go both ways.

“However, I’ve also seen comedians be harassed on stage, and that behavior is very different from heckling … It’s threatening language that include issues such as sexual violence or rape, and it’s gendered attacks. I’ve seen audience members yell things about a comedian’s appearance, and weight and make rape threats while she’s onstage … Often women are told to ‘just get over it’ because heckling is part of a comedian’s job,” said Ashley Nicole Black in “The Subtle Harassment in Comedy No One’s Talking About in attn.

Reddit user u/Shcteve performs comedy shows in Bangkok for a primarily tourist audience. He observed that “drunk Brits and Australians are aggressively rude all of the time. A frequent thing I hear from this crowd is ‘well normally the hecklers are the best part of the show, they make the comic funnier.’ I guess that is common though in those countries.”

Reddit user u/ByeLongHair detailed a few times they were openly harassed and sexualized in the comedy world. One instance was with a married man who kept jokingly taking off his wedding ring in front of the others in their group. He was persistent despite there being no mutual flirting.

“I can only assume fellow comics assume women comics are down because we are labeled as ‘fun.’”

Deciphering what is comedy and what’s harassment, belittlement, misogyny, sexism or racism has been muddled for as long as comedy has been around. In 2017, quite a few comedians were called out for harassment. People like Louis C.K., Aziz Ansari, Jamie Foxx, TJ Miller and Jeremy Piven were all brought up during MeToo’s takedown of the powerful.

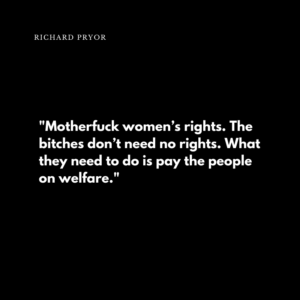

Fatty Arbuckle was accused of raping a woman and killing her by rupturing her bladder; this was the media’s first true experience of seeing the connection and gravity comedians hold on society. Lenny Bruce’s jokes got so intense he was deemed a “sick comic.” Richard Pryor outraged the LGBTQ community all the while railing against women’s rights. Eddie Murphy was called out for some of his old jokes that were against gay people. Bill Cosby’s mass of sexual assault led him straight to jail and disgrace. Even actor Kevin Hart withdrew from hosting the Oscars after old homophobic tweets he made resurfaced.

Graphic by Madison Miller

Oftentimes, the jokes that discriminate or attack a certain group of people are the ones called out by the public. But it seems like this is a great deal of comedy. The issues with comedy and harassment have always been blurry and the consequences often limited.

For the Chicago comedy scene especially, these issues hit close to home. According to an article from the Chicago Tribune titled “Women in improv comedy detail a culture of sexual harassment, silence,” it becomes clear that female voices in the comedy world are often silenced.

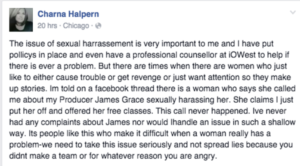

A 2016 Facebook post from Charna Halpern, founder and owner of iO Theater, opened a “floodgate of impassioned responses … women recounted unwanted sexual advances, inappropriate remarks and a persistent fear of retaliation if they spoke up.”

Initial Facebook post from Charna Halpern.

Chicago performers like Julia Weiss, who performs with one of Second City’s touring companies, said that the continuing atmosphere of gender harassment comes from casual sexism and unwanted sexual advances.

Former Chicago improviser Belinda Woolfson outlined the extent of the situation in the same Chicago Tribune article.

“I’ve had directors ask me out on dates and, when I’ve said no, they have punished me by taking away parts … some stopped talking to me completely. I’ve had my ass grabbed, I’ve been kissed against my will, I’ve received harassing text messages, and I’ve been sexualized on stage for ‘the sake of comedy’ too many times to count.”

Kachel said that there’s a certain kind of man that will “prey” on new female comics, usually open-micers.

Where do we continue to draw these lines that allow anything to go for the sake of “pushing deeper for comedy?” How do we end harassment in comedy if, for some comedians, it’s just the butt of a joke?

It’s clear that people need comedy and use it as a source of laughter during dark times. Recently, every platform is releasing a tirade of new comedy specials to cope with our current pandemic.

“Baptiste thinks its role is the same as it has always been … ‘to provide the balance to tragedy in the theatre that is art and life … to rationalise trauma; one of the most effective coping methods humans have in this crazy world. It’s the best alternative to politics and its censored, sycophantic, dishonest nature,’” said Stuart Jeffries in a Guardian article.

There is an argument that political correctness is destroying comedy or that “we’re not allowed to joke about anything anymore.”

“Other people claim that comedy is dying because they’re rightfully being called a hurtful jerk when they say unthoughtful hurtful jerk things,” said Kachel. “I think comedy should be able to tackle any sticky issue, but when you’re dealing with people in a small scene who are staying in a small scene because they lack the wit, fortitude and intelligence to properly handle said sticky issues, nothing really gets done besides people making lazy jokes that are usually hurtful.”

Graphic by Madison Miller

Humor and comedy are all subjective. But, is harassment and assault?

Whitney Cummings once said in an episode of her comedy podcast “Good For You,” which featured journalist Ronan Farrow, that “we expect our victims to be saints.”

But, what do we expect our comics to be?