“Before the march began, we seven strolled solemnly past the Vietnam Memorial. What Travis Levitt said there sums up our reasons for marching. As we stared, awestruck, at our own reflections in that immense wall, reading the etched names of the souls lost vainly in Vietnam, he whispered “It’s pretty powerful when you think that this is what can happen when you make a mistake like that.'”

-Chronicle Staff recounts their experience at an anti-war protest in 2002

Photo captured by a Chronicle reporter showing an anti-Iraq War protester walking alongside the Vietnam War Memorial.

In the history of American foreign policy, there are two glaring blemishes on the record of the nation known as the Leader of the Free World: the Vietnam War and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq . Both of these conflicts brought with them tremendous costs–obviously financially speaking, but also in terms of lives lost–as well as facing intense scrutiny from the public and press.

Set less than forty years apart, these two crises were covered by an eager and outspoken Chronicle staff, on a quest to showcase the immorality of both wars. There are obvious overlaps within these two stories–members of the Chronicle staff musing on the mistakes made in Vietnam a few months before U.S. forces rolled through Baghdad, for example–and yet there are significant differences: to the North Central students speaking out against Vietnam, the conflict perhaps had a closer feel to it, due to use of the draft.

New Men on Campus

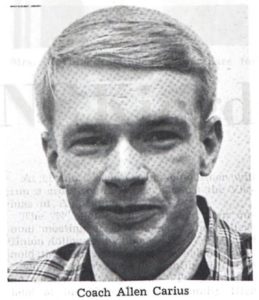

Al Carius as he appeared in a 1966 edition of The Chronicle. Carius’s arrival coincided with the escalation of North Central’s activism against the war.

It was Autumn of 1966 when an eager Al Carius arrived on the campus of North Central to coach the men’s cross country team. It was the beginning of a new chapter for North Central, a school that would become synonymous with running over the next 50 years.

But Carius’s arrival also coincided with some of North Central’s most turbulent years. The college was facing financial problems and student enrollment was slipping which threatened the college’s ability to survive. On top of the administrators’ woes, American involvement in Vietnam was rapidly increasing and students, if no one else, were taking notice.

Two summers ago, the USS Maddox, an American Navy destroyer performing surveillance off the coast of Vietnam, was given chase by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats, and responded with several warning shots. A small battle ensued when U.S. aircraft from a nearby aircraft carrier engaged the boats, leaving all three crippled as well as several NVA soldiers dead.

Two days later the ship reported they had been engaged again, and this time 22 torpedoes were fired at them.

Back in Washington, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara urged President Johnson to take action. Hours later the president ordered airstrikes against North Vietnamese military targets along the coastline. Johnson then took his case to Congress, where he sought a resolution for further action against North Vietnam and was successful. Unanimous in the House and receiving only two dissenting votes in the Senate, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution granted Johnson the power to take “all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

As military operations escalated, so too did the Chronicle’s coverage of the war and their pointed editorials. One early editorial in particular, “Democracy Lacking in the U.S. Draft”, attacked what had already become one of the most unpopular aspects of the war. Americans rejected the draft for turning the conflict into a poor man’s war. College students could easily get deferments to avoid service, while the sons of well-connected families were able to serve in their state’s National Guard or in the reserves. Former President George W. Bush, for example, whose father was member of the House of Representatives at the time, was able to make it into the Texas Air National Guard where he never ran the risk of being sent overseas.

North Central Professor Gerald Gems served in Vietnam between 1967 and 1968. Photo by North Central College.

The notion of the Vietnam War being a poor man’s war was the biggest factor that turned Dr. Gerry Gems against the war. Today Gems is a professor of kinesiology at North Central, a few weeks from retirement; but 50 years ago–from August 1967 through May 1968–he was half way around the world, leading a platoon of marines through the jungles of Vietnam.

Gems says he came from a working class family, and grew up in a nearly homogeneous neighborhood comprised of minorities and lower-class families. He says he quickly realized that these were the kind of people who were over there doing the fighting.

Dr. Steve Macek, too, arrived at the campus of North Central in autumn–though of 2002–during the peak of the the prelude to war with Iraq. Without hesitation, Macek thrust himself to the center of North Central’s anti-war movement. He served as the faculty sponsor to a social justice group that was responsible for much of the activism on campus.

Macek says one of the groups most notable events came in the form of a demonstration in which 25 students marched from campus to the corner of Washington and Chicago.

Macek says one of the groups most notable events came in the form of a demonstration in which 25 students marched from campus to the corner of Washington and Chicago.

Macek also organized an event he intended to be a forum or debate over American military action against Iraq. But if it’s any indication of how the campus felt about war with Iraq, Macek essentially failed to find a pro-Iraq War voice, though not for a lack of trying. He went so far as to seek out “representatives of the Republican Party and no one would come out and talk.”

“Eventually what happened was Tom Cavenagh agreed to argue that position even though he didn’t believe it,” says Macek. Indeed, the Chronicle notes in its recap of the event that Cavenagh, a professor of business law and conflict resolution, participated “despite his own sentiments, to create a more balanced debate”.

Students March

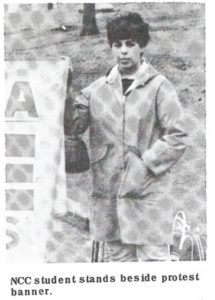

NCC student at 1967 NYC anti-Vietnam march

In April of 1967, 15 North Central students journeyed from Naperville across the country to New York City,

“garbed in a collection of sandals, ponchos, army surplus jackets, and shoulder-slung sleeping bags, the group looked like group of Mexican migrant workers moving to a different field”.

Their trip turned out to be an eventful one: on the way there, one bus scraped along 270 feet of guard rail when its steering linkage was compromised. The other bus got a flat tire, which took two hours to fix. Half a block after getting it patched they got another flat. But once they got there, the march was successful and ended with a speech delivered by Martin Luther King Jr. at the United Nations Plaza.

The Chronicle seemed to make a small jab at the those who went though, when they wrote: “Whether all of the marchers were filled with ardor for the cause of peace cannot be determined; neither can it be determined whether New York’s liberal drinking law influenced anybody’s decision.”

While North Central’s response to the war was far from apathetic–especially given the school’s modest size–historians like Dr. Will Barnett say the larger picture of student activism and radicalism puts North Central’s response in perspective.

“I don’t think this would be a campus that was a hot bed of radicalism compared to a bigger school like the University of Illinois, or Wisconsin, or University of Michigan,” says Barnett .

For example, the experience of retired North Central philosophy professor Tim Morris shows how a larger, more radical campus reacted to the war. Morris was an undergrad at the University of Iowa during the late ’60’s and early ’70’s and a part of the student anti-war movement.

In 1970, A year that saw Richard Nixon expand the war into Cambodia and four college students infamously killed at Kent State, Morris and hundreds of other Hawkeyes shut their campus down after protests turned increasingly violent. In May, three hundred protesters blocked traffic on the highway and were later confronted by state police in riot gear. Later the university’s ROTC building had its windows smashed in by protesters. This was enough for the president to cancel final exams and send everyone home for summer a couple weeks early.

Hundreds of student protesters on the campus of the University of Iowa. The increasing protests forced the school to close its doors early in the Spring of 1970. Photo from the Libraries of Iowa.

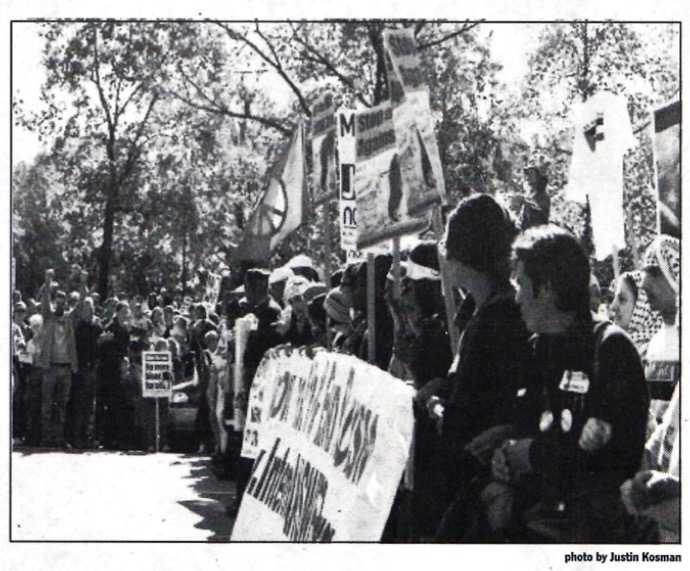

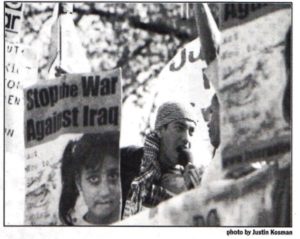

Thirty-five years after the march in New York, the next generation of North Central protesters assembled to take on the Bush administration and the imminent preemptive strike. This time seven NCC students made the 14-hour-long trek from Naperville to Washington D.C. where they were lost in a sea of more than 100 thousand protesters.

Adam Harris, a staff writer for the Chronicle, was one of the seven who attended the march, though his passion for making his voice was perhaps less than those around him. Writes Harris, “My first protest, an anti-war protest, and I didn’t even know what we were protesting. Okay, that’s not exactly true, but I certainly didn’t consider myself an expert on the subject. I’ve never voted (though I am registered), and, to be honest, I’ve never really cared about politics one way or the other.”

The scene at the October, 2002 anti-Iraq War march attended by members of the Chronicle.

But for what it’s worth, Harris left the march having been deeply impacted, writing ” I don’t think the greedy, oil-grubbing Bush Administration needs to inflict its wrath on a country that does not pose an immediate threat to us. I remember the bullies in elementary school, and I didn’t like them stealing my lunch money either.”

An Adversarial Press

In 1969, the story the broke that would irreversibly seal the war’s fate in the hearts and minds of countless Americans. In March 1968, an army unit led by Lieutenant William Calley was sent on a search and destroy mission to the Vietnam village of Son My. The soldiers found no trace of Viet Cong and took no resistence, but rounded up the villagers—children, the elderly and women included—and gunned them down. Estimates for the death toll hover around 500.

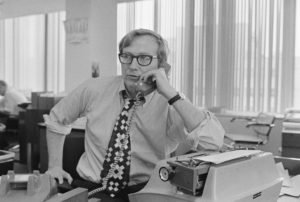

Seymour Hersh, pictured here in 1969, was responsible for breaking two major scandals that turned public opinion against these wars.

The army was able to keep the massacre under wraps for more than a year before the efforts of a soldier from a different company who had heard of the massacre reached a set of ears that would listen. That person was Seymour Hersh. It was the first big story for the journalist whose accomplished career spans four decades, but certainly not his last.

In 2004, Seymour Hersh once again ascended to the national spotlight with his article that revealed the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib. After the invasion, Abu Ghraib prison was home to more than 7 thousand prisoners, and maintained by the U.S military police. Even from its first days, there were whispers by international groups of abuse being carried against prisoners. But it wasn’t until the public saw photos of prisoners on leashes, others smeared with human excrement, and a couple forced to engage in sexual activities with their fellow inmates that there was widespread outrage. And then Hersh’s story a couple days after the pictures were published blew the lid off the story.

Interestingly, the latter of the two stories received significantly more attention from The Chronicle, even though today Mai Lai is perhaps still better known that Abu Ghraib. In 2004, the year Hersh’s story broke, the Chronicle wrote 5 stories that related the scandal. By contrast there weren’t any stories written about Mai Lai the year it broke and it only came up twice in stories during the remainder of the war.

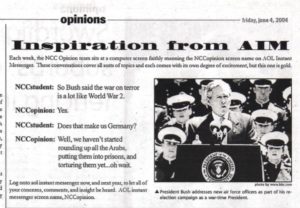

Screenshot of a June 4, 2004 edition of The Chronicle. During the popularity of online chatrooms, The Chronicle operated under the name NCCopinion as a way to directly engage with students. This back and forth shows the Chronicle account referencing the Abu Ghraib scandal in comparing America with Nazi Germany.

The Chronicle had a field day with the story, using it to continue their narrative of American hypocrisy in a land they didn’t belong.

The first article about the scandal emerged in May of that year, about a month after the story first broke. In the somewhat amusing article titled “America: Land of the Free, Home of the Blameless”, columnist Ryan Peters decried the idea of the scandal representing a few bad eggs, but rather following up on Hersh’s claim the acts came from the top down. He writes, “Common sense would tell anyone who took a passing glance at the photos coming out of Abu Ghraib that the techniques employed by military personal suggest authorization and sanction, not ‘renegade’ behavior. Most soldiers leaving for battled do not pack dog leashes along with their socks.”

The war wanes and coverage declines

As the wars dragged on–both conflicts would last around a decade–less and less articles appeared in the Chronicle, though for different reasons.

During the late ’60’s, the Chronicle experienced something of an existential crisis over uncertainty of how to cover the era’s tumultuous events and campus reactions to them. This was highlighted in “150 Years. A Promising Start.”, which wrote:

The Chronicle found itself in the middle of heated student debate and disagreement over covering national issues in the paper. The editors decided that the paper would not print national news or reactions to it, but would stick to local issues that “pertain to the campus and student affairs”.

The Chronicle kept their word, evidenced by a sharp decline in stories about the war. In 1969, 21 stories were published about the war; the following year that number was just four, and sure enough, they all related to North Central, be it special lectures delivered by faculty or the case of a Vietnamese woman who fled her country who was going to give a speech.

The War in Iraq had a different fate, however; Chronicle coverage of the war essentially followed troop involvement. Coverage peaked in 2004, the year after the invasion and around the time the media realized there wasn’t a well thought out contingency plan nor were there discoveries of Saddam Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, that had been promised in the first months after the invasion. Coverage dipped for a couple years before shooting back up in 2007, no doubt coinciding with President Bush’s troop surge.