Ryan Schuring ’17 pursues a promising career in business. A quadruple major, his resume proudly boasts noteworthy internships, leadership positions and professional involvement. When mentioning his position as treasurer of the Illinois College Republican Federation, however, he hesitates.

“In this climate, it’s been tough to say you’re Republican,” says Schuring, who is also vice president of the North Central College Republicans. “And that’s not something I’ve always had to do.”

In the wake of the 2016 presidential election, Schuring fears partisan bias from potential employers. He recalls experiencing this same hesitancy in the classroom, with college faculty and with peers – though he has friends on both sides of the political spectrum.

“It used to be that people just thought, OK, you’re a Republican, you’re a Democrat, we’re all friends,” says Schuring. “A lot of people I know (now) won’t be friends with a Democrat; they won’t be friends with a Republican.”

This divisiveness of partisanship has been experienced by the political left as well as the right. President of the North Central College Democrats, Kevin Oyakawa ’19 recalls experiencing partisanship in nearly all aspects of his student life so far – even those that shouldn’t be. Clad in suit and tie, he heads to DePaul University to represent his fellow Democrats in a debate regarding free speech on college campuses – an issue that, among many, has turned inexplicably and aggressively partisan in recent years.

“Seeing partisanship on a college campus is something I wasn’t expecting to have to deal with already,” says Oyakawa. “There are a lot of topics out there that have turned partisan that should not be.”

“We’re not talking with each other, we’re talking at them,” says Schuring. “It’s a lot of personal attacks… There’s no exchange of ideas.”

The 2016 presidential election has garnered more partisan animosity than at any point in nearly a quarter of a century. According to Pew Research, twice as many Republicans and Democrats say they always disagree with their opposing party’s views compared to those who say they always agree with their own party’s policies. This political polarization has reached a new height since the Reconstruction Era in 1885.

Republican and Democratic voters, it seems, can only agree to disagree: at least 81 percent of registered voters of both Republican and Democratic parties say they disagree with their opposing political party not just on plans and policies, but on basic facts and statistics. In the midst of the most heated and aggressive political election in modern American history, partisans no longer define themselves by who they are but, and with bitter and ferocious conviction, by what they are not.

“We are at a point now where it’s not just that the core ideology and the platform of the parties are so different from one another but that the voters […] feel that if the opposing party is in control, they’re going to ruin the country,” says Dr. Suzanne Chod, North Central College associate professor of political science. “It used to be that we just disagreed on the means to achieve the same goals. Now we’re disagreeing on the goals and even more starkly disagreeing on the means.”

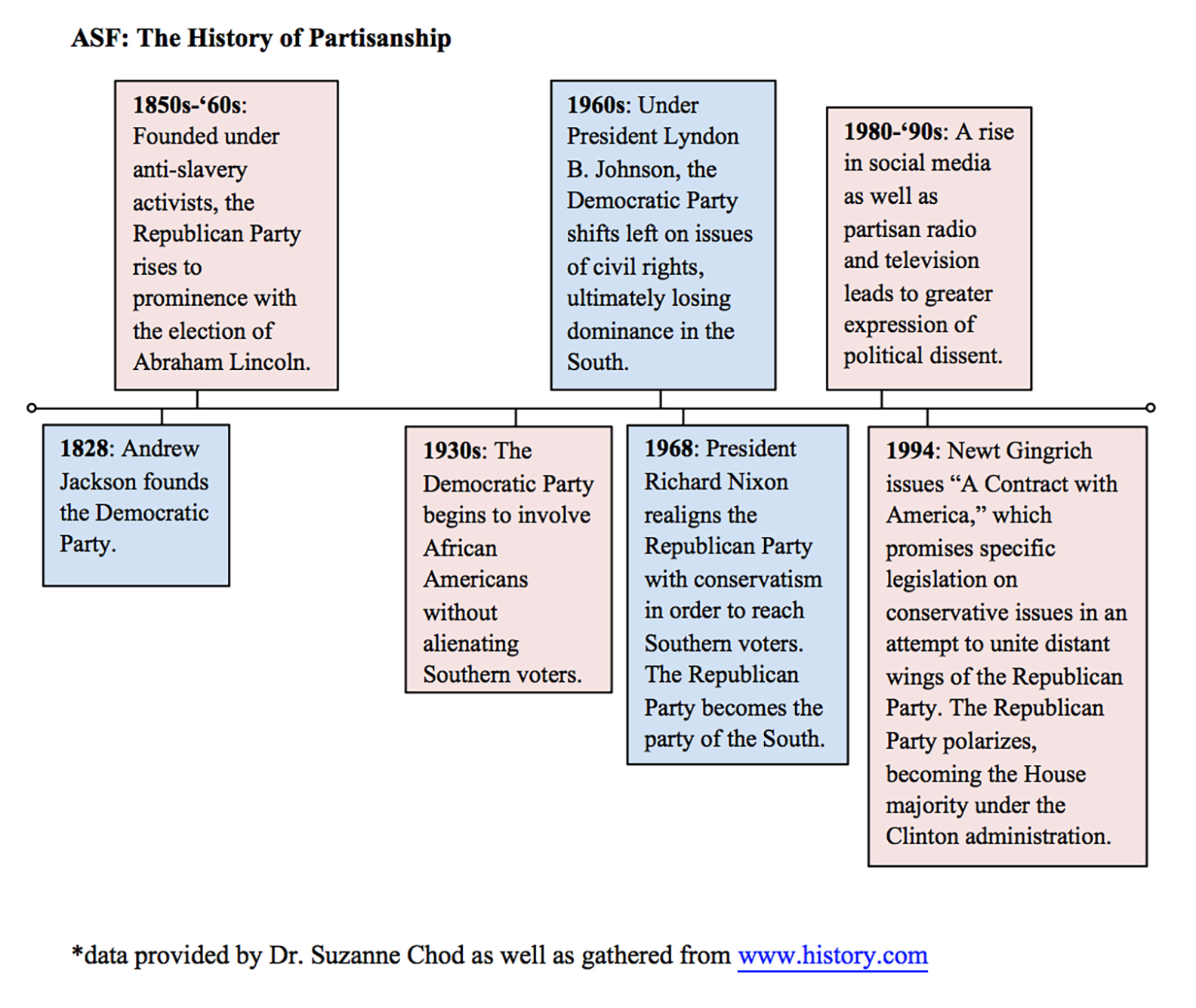

From a political perspective, recent political animosity roots itself in the radicalization of party identities in recent elections. According to the political science theory known as conditional party government, when one party becomes more cohesive than the other, the opposing party will respond by becoming cohesive in the other direction.

In the 1960s, President Lyndon B. Johnson shifted the Democratic Party toward the political left on issues of civil rights, creating a more progressive Democratic platform. As a result, the party lost favor with conservative Southerners, who then turned to the Republican Party for revision. This event ignited the partisanship we see today. More recently, in 1994, Republican Congressman Newt Gingrich polarized the Republican Party further toward the political right through his passage of a “Contract with America,” which promised active legislation on conservative issues. Reactively, the Democratic Party became more progressive within the last decade.

As one party shifts right, the other shifts left; and vice versa. Since the 1990s, this political game of tug-of-war has slowly isolated each party from the other, instilling overwhelming partisan identities in American individuals. As a result, partisans have begun to define themselves not only by what they are but by what they are not: Democrats are the opposite of Republicans; Republicans, the antithesis of Democrats.

“I often liken it to sports fans,” says Chod. Firm establishment of partisan identity coupled with years of distancing on the political spectrum has resulted in Americans who not only cheer and root for their own team, but loathe and boo the other.

From an urbanist perspective, political animosity grows too from cultural or political “sorting,” or segregating. According to Dr. Ann Keating, North Central College professor of history, within the last half century, people have gained the option to choose where they wish to live. Partisanship has played a crucial role in this decision: Republicans prefer to surround themselves with other Republicans, and Democrats with other Democrats, resulting in partisan segregation throughout the country. Americans are, quite literally, choosing the company they keep.

“Since the 1970s, we have been sorting ourselves politically,” says Keating. “Today, fewer people (of opposing partisanships) are neighbors. (As a result), there has been a ramp up of animosity.”

This option to choose since the 1970s extends beyond real estate – education, religion, even relationships are now more readily left to the choice of the individual. More than two-thirds of registered Democrats and Republicans in the 2016 political election say their spouse or partner will vote for the same presidential nominee.

Choice of news consumption has played an even greater role in the divisiveness of partisanship. Up until the mid- to late-twentieth century, Americans received news from a small pool of nonpartisan sources, primarily local newspapers. Today, a decline of newspapers and the rise of social media has allowed consumers to choose where they wish to receive their news and entertainment as well as what information they wish to receive and accept.

This ability to choose appeals to one’s confirmation bias, or the internalization of information that supports one’s beliefs as well as the rejection of information that does not. The rise of partisan news outlets, such as the left-leaning MSNBC and the right-leaning Fox News, has further fueled Americans’ desire for bias confirmation as well as their hate for dissenters. With information only becoming more rapidly available from even more partisan sources in the 21st century, Americans choose likeminded-ness in the face of other adversarial options.

“When you look at how the media portrays certain issues, they say that you have to be on one side or the other,” says Oyakawa. “There’s no in-between; there’s no compromise. If you do compromise, you’re considered a loser.”

However, while animosity has dominated the political climate in recent years, it is not the default. Political compromise and understanding in partisanship can be re-achieved through empathy.

“Keep it civil,” says Schuring, “try to focus on the facts and take everyone’s experiences into account.”

“There definitely can be meaningful conversation even if you’re far left or far right,” says Oyakawa. “If you are able to empathize then you will be able to compromise, but it takes a lot to empathize with someone. It takes time. It takes research. It takes a lot to see fully the other side of the spectrum’s viewpoints.”