Artist Alley at the Chicago Comic and Entertainment Expo (C2E2 for the in-crowd) is a flurry of activity. The massive convention hall is brimming with new and established artists and writers proudly displaying themselves in front of stacks of their work. Harley Quinn cosplayers and comic book aficionados dash down the aisles, while creators do their best barking. “Hey, check out my comic! Think of it as Calvin and Hobbes meets Fatal Attraction,” shouts a caffeine-charged creator as some perplexed shoppers wander by. Their job, first and foremost, is to try their best to coax potential fans to saunter over and take a look at their art, and maybe buy some, please.

C2E2 main hall. Photo by Peter Medlin

Andy Eschenbach is an up-and-coming writer situated a bit toward the back of the hurricane, standing behind his booth, waiting for fans to come by. As someone relatively new to the comics industry, he doesn’t command lines of people itching to meet him, instead he refines his pitch as onlookers ask him who he is and what he is doing.

ACT I: PANEL SYNDICATES AND SELF-PUBLISHING

More importantly, being new in the industry means that he isn’t published by one of the major houses, he isn’t paid for his work. He self-publishes his comics. Self-publishing within professional writing exists for largely one of two reasons. One: as a way for new writers to find their voice and put out their work which hopefully leads to it finding a home at a publisher, or two: it is done by established writers to embrace their independence and dictate their own market, masters of their own destiny.

For professor Richard Guzman, it’s the latter that leads him to self-publishing his work on his extensive website. Save for the graying temples, he is, in many ways, a paragon of the modern writer. He has written poetry, a comprehensive history of jazz, even several scientific textbooks. He’s diverse, eclectic. Published for many years, Guzman has shifted his focus online and to self-publishing recently, choosing to forgo publishers and do his own thing. Here, Guzman talks about his migration online:

Other established writers have gone the way of Guzman as well. In 2013, acclaimed writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Marcos Martin launched Panel Syndicate, a platform they used to release their digital comics with a revolutionary price system. They offer their top-of-the-line stories to customers for “whatever the hell they want to pay.” You could download them for $1 or $100, you could pay nothing, but rest assured whatever you do pay goes directly to the creators.

North Central College junior Maya Rothman doesn’t have delusions that her self-published book “Cracked Wide Open” will have her swan-diving into mounds of money. In fact, she hasn’t dropped the $11 and change on a copy of her own book. “For me, I just want to share my ideas, but if someone buys a copy, that’s great, too,” said Rothman. “I tried to go through finding a publisher and they didn’t really care about the writing itself, they just cared about if my work was marketable.”

ACT II: MARKETING AND REAL MONEY

Marketing, it turns out, is an essential attribute to self-published authors, especially if they are wishing to garner income from their work. “If you self-publish your book, you are not going to be writing for a living. You are going to be marketing for a living,” said author Ros Barber in an article for The Guardian. “Self-published authors should expect to spend only 10 percent of their time writing and 90 percent of their time marketing.”

Maya Rothman’s e-book. Information via lulu.com

Never mind the self-publishing path, traditional publishing isn’t exactly a goldmine either. Brian Michael Bendis echoes that sentiment in his comics guide “Words for Pictures.” If that is the reason you are getting into writing in the first place, well, you missed your exit for engineering. “Money, real money, doesn’t factor into the equation for 99 percent of the people who write,” said Bendis.“I, personally spent half of my career not making a dime and the last half of it lucky I could provide for my family.”

That experience is not exclusive to comics. In poetry, reality may be even more stark. “I mention what the most I ever made from a poem was, but for most poems it’s $0,” said Dr. Rebecca Stafford, author of two extensive collections of poetry. Here, she breaks down the strenuous process of getting published and making money in the world of poetry, and how difficult it is for unknown and economically disadvantaged poets to bust into the business.

ACT III: HOOP JUMPING AND ALTERNATIVE AVENUES

The painstaking of publishing that Dr. Stafford describes is about as drawn out in self-publishing, as well, especially if your funding isn’t already banked. Rothman’s short, sub-50 page book took a full year from conception to publication last year. Eschenbach’s publishing timeline grinds to a slow churn due to the collaborative nature of comic books. “I’ve had single books take anywhere from four months to over a year – even when each party works at a decent pace,” he said. “Sometimes there are gaps between when team members can work. Plus, there’s the issue of saving up the money.”

Eschenbach’s publishing timeline grinds to a slow churn due to the collaborative nature of comic books. “I’ve had single books take anywhere from four months to over a year – even when each party works at a decent pace,” he said. “Sometimes there are gaps between when team members can work. Plus, there’s the issue of saving up the money.”

That awkward waiting game does not disappear once you get published, actually it can be longer, says professor Zachary Jack, author of over 20 books spanning any genre imaginable. Jack has shoulder-length brown hair that lays neatly, just at the line of his jacket. If you were casting a college English professor, an overzealous producer might turn him away for being just a bit too on-the-nose. Sometimes, he explains, you can have a book in limbo for up to three or four years. He expounds further here in his notoriously disheveled office, hoping there is nothing incriminating among the loose papers and books spilled on the shelf behind him. Here’s to it:

Online publishing at least strips away some of the gatekeepers that come with traditional publishing and allows for alternative avenues to your audience, including some that didn’t exist until just a few years ago. Independent film and music have recently found success utilizing crowdsourcing alternatives such as Patreon, Indiegogo and Kickstarter. And following suit, some writers have already gone to Kickstarter to fund books, while others take their talents to Patreon for a subscription based method that gives their “patrons” exclusive content depending on their varied tiers of support. While generally, writing has followed a more formal path thus far, Jack is confident that writing is headed in a less traditional direction, inspired by independent artists in other media.

There are some, even other authors who believe that self-publishing and these growing, alternative brands of publishing put a damper on the quality that people expect out of published, professional writing. That weaseling around traditional gatekeepers simply means that your writing isn’t up to snuff.

Growth of conventions: red dots represent new cons sprung up since 2000. Not including the countless small-town cons across the nation.

Author Samita Sarkar begs to differ in her Huffington Post article “Self Publishing: An Insult to the Written Word or a Boon to the Industry?” “Just because some find it to be the system that works best for them doesn’t mean it should be the only system available,” she says. “To have just a handful of major players dictating who gets a piece of the publishing pie is a recipe for disaster.” The self-publishing protesters also assume that these authors renounce professional editors and designers, which Sardar dispels citing the common practice of editors and designers taking on freelance work.

ACT IV: HARD LESSONS AND CONVENTIONS

Online business marketplaces like LinkedIn use common connections and groups to introduce writers to others in their field, and social media networks like Twitter are great for up-and-coming writers to follow and interact with pros in your industry (such as these free agent editors). One of author Carol Tice’s tips for getting noticed on Twitter on her blog “Make a Living Writing” is to search out influential people in your niche, and make sure that they occupy a nice spot on your timeline.

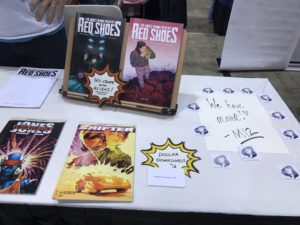

Despite the internet ubiquity that we exist in today, in-person conventions (like C2E2) and fairs are still prime time for writers to make connections with other artists and editors, as everyone you need to talk to setting up shop at tables within arm’s reach. And hey, guess what, you already have your portfolio with you.

Book fairs are similarly valuable for writers outside of comics, as English professor Lisa Long found out when at the first fair she attended. Her friend shepherded her over to meet a group of editors, which led to a career breakthrough.

Conventions used to be one of the only ways to get your work in the hands of the people that can get you hired, but in recent years, the internet and social media has allowed creators to cultivate audiences and establish a presence on their own. However, it’s hard to argue that the personal connections that conventions offer don’t hold weight anymore. “Nothing beats a face-to-face interaction (especially a genuine one), and social media can only be taken so seriously,” said Eschenbach. “Websites work for making your work accessible, but handing someone a portfolio or finished book is better.

Andy Eschenbach’s self-published comics. Photo by Peter Medlin.

”These career breakthroughs can happen at any moment, but even for seasoned artists, you never know what is going to hit or catch on. A poem that you know is sure fire could fizzle out, but then another that you’re not so sure about could be snatched up in an instant. “Publishing, especially in the creative field,” says Richard Guzman. “There is a sense in which it doesn’t quite have to make total sense. There has to be something that demands a leap of imagination.”

The sidesteps and detours that your career takes can be deflating. The checks that Guzman’s jazz history radio program paid him two months rent could have been two years. But, in the moment those two months were the ones that mattered. Every writer is going to have their fair share of grotesquely missed opportunities, if you choose to look at them like that.

“If you’re not falling, you’re not really trying hard enough.” said Joe Quesada, former Marvel editor-in-chief in “Words for Pictures.” “There’s an old adage that says that the most successful people you meet have failed more than anyone you know, and I firmly believe that to be true.”

ACT V: TWIN PASSIONS AND LAST WORDS

Even as Dr. Stafford sits comfortably in her tidy beige office with two full-length poetry books in her repertoire, she has still had more than her fair share of hard times. In fact, she feels that way right now, caught in an ephemeral creative rut, after getting settled in a new job and welcoming a child. She’s had to negotiate the themes and aesthetics that she used to write about and how maybe they aren’t who she is anymore. She even had to shelve the book she prepared for her thesis.

At the end of the day, you can only do so much, and your work will speak for itself. “The vast majority of writers live that struggle every day,” said Zack Jack. “How to balance your twin passions, for your day job, whatever that is and their passion for writing.” In “Words for Pictures,” Brian Bendis likes to refer back to a Peter Gabriel quote that he carries with him, “Success is a fickle mistress. If you go chasing her, she will ignore you. If you leave her alone and just go about your business, she might come looking for you.”

Editor’s note: All photos, videos, audio, editing and design by Peter Medlin